The following article appeared in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal. The Amateur referenced in the article is ARRL’s Rick Lindquist, N1RL.

The following article appeared in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal. The Amateur referenced in the article is ARRL’s Rick Lindquist, N1RL.

In This Power Play, High-Wire Act Riles Ham-Radio Fans New Use for Lines Sparks Tension With Operators; ‘Firestorm’ in Penn Yan

By KEN BROWN

Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

March 23, 2004; Page A1

Rick Lindquist drove down a street in a New York City suburb, ignoring the snow swirling around his car and twirling the dial on the ham radio mounted to the side of his dashboard. The radio picked up an operator in Minnesota discussing antennas, the Salvation Army’s daily emergency network check and then the time, as broadcast from Colorado by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

As the car turned onto North State Road in the village of Briarcliff Manor in Westchester County, the voices faded, replaced with whirs and wahs — what could have been sound effects from a 1950s science-fiction movie. The source, according to Mr. Lindquist, was right outside the window: the power lines running alongside the road.

Owned by Consolidated Edison, the lines transmit not just electricity but data, much like phone and cable-TV wires. The utility is testing a system for reading meters, probing for outages and potentially offering high-speed Internet access to its customers via their electrical outlets. The interference from the power lines “ranges from very annoying to that’s-all-I-can-hear,” contends Mr. Lindquist, 58 years old, who often taps out Morse-code messages as he drives.

In a clash between the dots and dashes of the telegraph and the bits and bytes of the Web, the nation’s vocal but shrinking population of ham-radio operators, or “hams” as they call themselves, are stirring up a war with the utility industry over new power-line communications. Hams have flooded the Federal Communications Commission with about 2,500 letters and e-mails opposing power-line trials. In a letter to the FCC, the American Radio Relay League, a ham-radio group with 160,000 members, called power-line communications “a Pandora’s box of unprecedented proportions.”

The league has raised more than $300,000 from nearly 5,600 donors since last summer, to pay for testing, lobbying and publicity to spread the word about the perceived threat. A half-dozen hams even confronted FCC Chairman Michael Powell, a big advocate of the power-line technology, when he visited a test site near Raleigh, N.C., earlier this month.

The problem, most ham operators contend, is that power lines weren’t built to carry anything other than electricity. Telephone and cable-TV lines are either shielded with a second set of wires or twisted together to prevent their signals from interfering with other transmissions. But signals sent over electrical wires tend to spill out, the hams contend.

The FCC and the utilities say new technologies have eliminated the interference and accuse the hams of exploiting the issue for their own gains. “We haven’t seen the sun darken and everything electrical turn to white noise and haze during a deployment,” says Matt Oja, an executive at Progress Energy, whose test Mr. Powell visited. “This is a fairly vocal group that has been whipped into a frenzy by their organization.”

The controversy comes at a sensitive time for the hams. Not too many decades ago, ham-radio operators were on the cutting edge of communications technology. They chatted with people in far-flung places at a time when long-distance calling was still a luxury. They spread word of disasters that otherwise might have taken days to reach the public. In the age of e-mail, wireless Internet access and cellphones that double as walkie-talkies, many operators worry that their hobby will fade away.

To become a fully licensed ham operator, people still need to learn Morse code, though that requirement likely will be dropped soon after more than a decade of debate. Aging hams, who built crystal radio sets as kids or were radio operators during World War II, are dying. Fewer youngsters are replacing them. Armed with powerful computers, today’s young tinkerers grow up to be tech geeks, playing videogames and writing software.

The American Radio Relay League has seen its membership shrink to today’s 160,000 from a peak of 175,000 in 1995, and the average member is in his mid-50s. The group estimates that there are about 250,000 active ham-radio enthusiasts. Hams always have been a quirky bunch. They haunt a series of short-wave radio frequencies set aside for them by the federal government in the 1930s. Other slices of the spectrum are reserved for AM and FM radio, broadcast television, cellphones, and police and fire departments, among other uses.

Hams take great pride in radioing around the world. One favorite game: trying to contact someone in each of the 3,000-plus counties in the U.S. Mr. Lindquist is so enthusiastic about ham radio that he vacations in spots such as Whitehorse, the capital of Canada’s Yukon Territory, so other hams can claim they made contact with that city.

Ed Thomas, the FCC’s chief engineer, says the commission has spent a year listening to the hams’ concerns about power lines and is getting frustrated. “Why is this thing a major calamity?” he says. “And honestly, I’d love the answer to that.”

Companies such as Con Ed and Progress note that current FCC regulations call for systems to be shut down if they interfere with hams. The radio operators agree the rules are clear, but they fear they will be rescinded or not enforced.

Con Ed says its system in Briarcliff Manor doesn’t interfere with the hams and maintains that, in two years of testing, it hasn’t received one complaint. But the American Radio Relay League says it did mention this system in its letters to the FCC, and it has been complaining about it on its Web site.

The hams have been quick to act wherever systems are being rolled out. Just days after Penn Yan, a town of 5,200 that sits amid New York’s Finger Lakes, approved a plan to test power-line Internet access, “the firestorm started with the ham-radio operators — letters, e-mails, telephone calls saying, ‘You can’t do this,’ ” recalls Mayor Doug Marchionda Jr.

Hoping to keep everyone happy, he approached David Simmons, a local ham and owner of an electronics store that sells radio gear. They surveyed the town before the trial began to get base readings of interference. They even pinpointed a spot that had bothered police and firefighters for years, tracing it to refrigerators at a local supermarket.

With the refrigerators fixed and the power-line system in place over nine blocks of Penn Yan, Mr. Simmons is satisfied that there is no interference and now favors the new technology. “This thing has caught quite a buzz,” he says. “It’s just so much negativity out there.”

Tom Gius, a ham-radio operator in Alpine, Texas, sees the power lines as a threat to the public services that hams provide. When hailstorms sweep through each spring, Mr. Gius heads to the local radio station, while other hams fan out to the north, south, east and west. They communicate by radio, and Mr. Gius passes information to the radio station. “We won’t be able to understand each other, it’ll be so noisy,” frets Mr. Gius, a 60-year-old retired broadcaster.

Write to Ken Brown at ken.brown@wsj.com

WA1I writes on K1USN-list:

WA1I writes on K1USN-list:

Members of the South Shore Fox Hunters held a successful hunt on March 12 near the Monponsett Ponds. Roy Logan, KB1CYV and George Davis, KC1FZ were hiding on a boat ramp off Route 58.

Members of the South Shore Fox Hunters held a successful hunt on March 12 near the Monponsett Ponds. Roy Logan, KB1CYV and George Davis, KC1FZ were hiding on a boat ramp off Route 58.  Bill Ricker, N1VUX wrote on CEMARC-list:

Bill Ricker, N1VUX wrote on CEMARC-list: “Bo” Budinger, WA1QYM writes on PART/WB1GOF-List:

“Bo” Budinger, WA1QYM writes on PART/WB1GOF-List: FARA’s 2-meter Slow Speed CW Net is enjoying success, according to Falmouth ARA’s John Gould, WX1K. Gould reports that the weekly net received “4-5 check-ins.”

FARA’s 2-meter Slow Speed CW Net is enjoying success, according to Falmouth ARA’s John Gould, WX1K. Gould reports that the weekly net received “4-5 check-ins.”  Members of the Southeastern MA ARA are meeting on Sunday, March 28 to landscape a portion of the club house property. Plans call for grass and sod work as well as driveway repair. According to Dave Dean, K1JGV, the driveway will be repaired with stone dust the club has stockpiled. Also, a large portion of the driveway will be overlaid with 3/4-inch stone.

Members of the Southeastern MA ARA are meeting on Sunday, March 28 to landscape a portion of the club house property. Plans call for grass and sod work as well as driveway repair. According to Dave Dean, K1JGV, the driveway will be repaired with stone dust the club has stockpiled. Also, a large portion of the driveway will be overlaid with 3/4-inch stone.  Mark your calendars for the 3rd New England QSO Party, May 1-2, 2004.

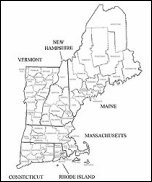

Mark your calendars for the 3rd New England QSO Party, May 1-2, 2004.

Terry Stader, KA8SCP writes on CEMARC-list:

Terry Stader, KA8SCP writes on CEMARC-list: The following article appeared in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal. The Amateur referenced in the article is ARRL’s Rick Lindquist, N1RL.

The following article appeared in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal. The Amateur referenced in the article is ARRL’s Rick Lindquist, N1RL. The Framingham Amateur Radio Association has been officially renewed as a Special Service Club.

The Framingham Amateur Radio Association has been officially renewed as a Special Service Club.  The Framingham Amateur Radio Association had another successful License In A Weekend class March 12-14, according to FARA’s Lee Gartenberg, K1GL.

The Framingham Amateur Radio Association had another successful License In A Weekend class March 12-14, according to FARA’s Lee Gartenberg, K1GL.  Eastern Massachusetts Section Manager Phil Temples, K9HI has written on opinion piece entitled

Eastern Massachusetts Section Manager Phil Temples, K9HI has written on opinion piece entitled  Bill Ricker, N1VUX has updated the Eastern Massachusetts Field Day web site at

Bill Ricker, N1VUX has updated the Eastern Massachusetts Field Day web site at